An Ode to a Woman Who Helped Pave Our Way

3.17.2023

“While we are impressed with your credentials, we are looking to hire a man for this position.”

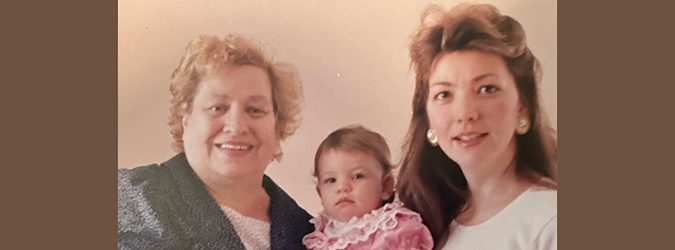

My grandmother Ada practiced law starting in the late 1940s in Brooklyn, New York. Grandma was born in Southern Italy and moved to the United States through Ellis Island when she was four years old. Her family settled in upstate New York, where she spent the rest of her childhood.

Grandma Ada was an exceptional student. She was featured in the local newspaper for attaining the highest average score for the New York State Regents exams. She was valedictorian of her high school class.

Because Ada was one of five daughters, with no sons, her father took her under his wing as his apprentice. Grandma assisted her father with the Italian-American newspaper he ran.

While she had an interest in journalism, she continued her education and earned her college degree. While attending college, in order to earn money, Ada worked in a military defense factory during World War II. When the war was over, despite having been trained and working in these factory positions, Ada and all her female coworkers were expected to immediately step away from their positions for men returning home. She felt this was an injustice. Growing up in a family with only daughters, she was raised by parents who did not subscribe to gender norms and limitations. Ada was taught and believed one should be judged based on their merit and ability. After college, she decided to pursue an education and career in law.

In the mid-1940s, Grandma moved to New York City to attend St. John’s University School of Law. She did not know of other women attorneys before attending law school and may have met only one other female law student while attending St. John’s. In the 1940s, society did not view it as acceptable for women to attend graduate school. She was not well received by professors or her classmates. Ada would say she had to “work ten times harder” than her male counterparts to earn the same grades. She was not afforded the same respect by her professors as her male classmates.

Grandma was the only woman in her graduating class. Despite her stellar academic record, her first position out of law school was secretarial because no one would hire her as a lawyer. After a year or two, Grandma had no choice but to open her own law firm in Brooklyn.

My grandfather, Ada’s husband, had a real estate firm in their close-knit Brooklyn neighborhood, and he referred his clients who needed legal services to Ada, enabling her to go out on her own. She ran her law firm as a general solo practitioner for the next 40 years. Ada practiced criminal law, family law (divorces and adoptions), disability law, wills/trusts and estates, and handled real estate and corporate transactions. Having a general law practice was common in those days.

While she never revealed this during her lifetime, my grandmother faced blatant sex discrimination when she entered the legal field in the late 1940s.

The attitude of Ada’s male counterparts in law school and when practicing law was that she did not belong in the field. Ada felt she was treated as a second-class citizen by judges and opposing counsel – all of whom were men. They could not believe she had the audacity to be in their field, in their space. They would go out of their way to give her a hard time. Fortunately, Ada was motivated by the naysayers, and she worked even harder. After her death, rejection letters from a New York district attorney’s office and a Manhattan law firm were found among her possessions. Both letters stated that, while the employers were impressed with her credentials, they were looking to hire only men for attorney positions. There can be no question that Grandma’s only choice was to hang out her own shingle in order to practice law.

Clients approached Ada knowing that they were going to be retaining a female attorney because her name was on the door. She had to charge less than her male counterparts. However, her clients were very loyal – they used her over and over again for all of their legal service needs. She often took on women clients whom male attorneys refused to work with or disrespected.

Grandma Ada had a brilliant legal mind and was fluent in five languages. As an attorney and a person, Grandma’s generosity knew no bounds. She would answer calls in the middle of the night to defend clients in criminal court. She was known to barter with her clients in exchange for her legal services. Grandma even went so far as to house clients in need in her own home.

In the mid-1960s, while raising her three children and running her law practice, Grandma ran for a seat in the New York State Senate. She even received an endorsement from the then-mayor of New York City.

Grandma Ada defied the prescribed expectations of women in the mid-20th century, enduring blatant gender discrimination prior to the enactment of equal employment opportunity laws. Her story inspired me to become a social activist and community leader starting in college, advocating for gender equality and earning a degree in women’s studies with a specialty in gender and social change. My grandma’s courage and career path also influenced my decision to attend law school in 2010. I am sure she would be astonished and pleased to learn that today more than half of law students in the United States are women. I am also certain she would be disappointed, though not surprised, that gender and sex discrimination still persist in the legal field. Eight years into my own legal career, I followed in her footsteps and opened my own law practice. I aspire to live up to Grandma’s legacy by using the law as a vehicle to help and empower others.

Let us celebrate the women who have paved the way for us in the legal profession. May we remember their history, appreciate the obstacles they overcame and be grateful that their efforts positively impacted our careers. More important, may we recognize that there is much more work to be done to achieve equality for women in the legal profession. I ask that you join me in continuing to clear the path for women in the hope that it will be less treacherous for those who travel down it after us.

Juliet Gobler is the principal of The Law Office of Juliet Gobler in White Plains, New York. Her practice focuses on wills, trusts and estates, and she has extensive experience in commercial litigation and Art. 81 guardianships. Gobler has been a feminist social activist, community leader and public speaker since 2008 while attending Stony Brook University, State University of New York. She is also a former president of the National Organization for Women’s Suffolk County chapter. This article appeared in a WILS Connect (2022, v. 3, no. 2), the publication of the Women in Law Section. For more information, please see NYSBA.ORG/WILS.